Understanding the Foundation of Steel Performance

Introduction

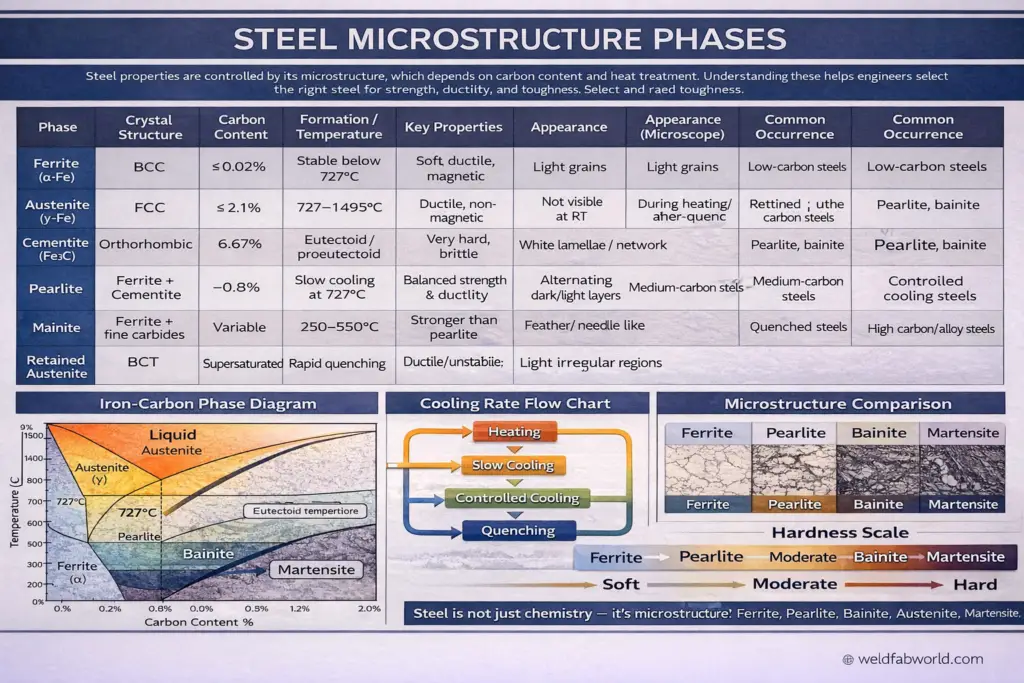

Steel is not simply ‘steel.’ Its performance characteristics—strength, ductility, toughness, and durability—are fundamentally determined by its microstructure. This microstructure, in turn, is governed by two critical factors: carbon content and heat treatment processes. Understanding steel microstructure phases is essential for engineers, metallurgists, and fabricators who need to select the right steel for specific applications.

The seven primary microstructure phases—Ferrite, Austenite, Cementite, Pearlite, Bainite, Martensite, and Retained Austenite—each contribute unique properties to steel. By controlling the formation of these phases through careful heat treatment, metallurgists can engineer steel to meet precise performance requirements for applications ranging from automotive components to structural beams and cutting tools.

The Seven Primary Steel Microstructure Phases

1. Ferrite (α-Fe)

Crystal Structure: Body-Centered Cubic (BCC)

Ferrite is the softest and most ductile phase in steel microstructure. With a maximum carbon solubility of only 0.02%, it forms a body-centered cubic crystal structure that is stable at temperatures below 727°C (1341°F). This low carbon content makes ferrite inherently soft and easily deformable, which is ideal for applications requiring formability.

Key characteristics:

- Magnetic at room temperature

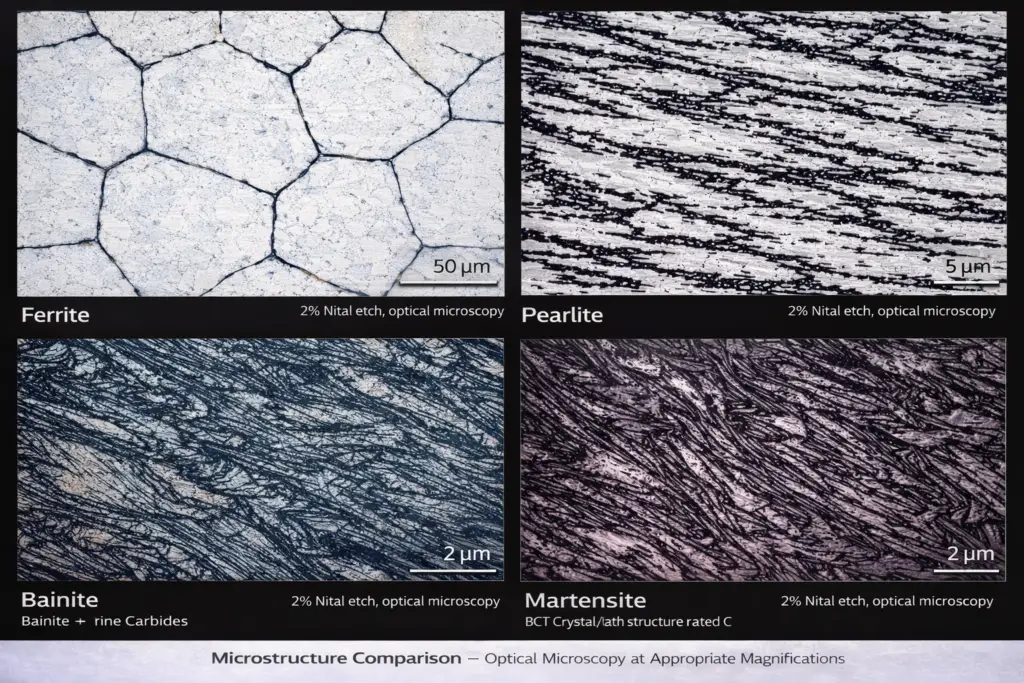

- Appears as light grains under microscope

- Predominant phase in low-carbon steels (< 0.25% C)

- Excellent for cold working and forming operations

2. Austenite (γ-Fe)

Crystal Structure: Face-Centered Cubic (FCC)

Austenite is the high-temperature phase of steel, stable between 727°C and 1495°C (1341°F–2723°F). It has a face-centered cubic crystal structure that can accommodate significantly more carbon than ferrite—up to 2.1%. This higher carbon solubility is crucial for heat treatment processes.

Key characteristics:

- Non-magnetic

- Ductile and easily deformed at elevated temperatures

- Usually not visible at room temperature in plain carbon steels

- Present during heating operations and hot working

- Can be retained at room temperature through rapid quenching or alloying

3. Cementite (Fe₃C)

Crystal Structure: Orthorhombic

Cementite, also known as iron carbide (Fe₃C), is an extremely hard and brittle intermetallic compound containing 6.67% carbon by weight. It represents the carbon-rich extreme of the iron-carbon system and plays a critical role in determining steel hardness.

Key characteristics:

- Very hard but extremely brittle

- Forms at eutectoid or proeutectoid temperatures

- Appears as white lamellae or network under microscope

- Primary strengthening constituent in pearlite and bainite

- Cannot exist independently in useful structural applications

4. Pearlite

Composition: Ferrite + Cementite (lamellar structure)

Pearlite is a two-phase microstructure consisting of alternating layers of ferrite and cementite. It forms at the eutectoid composition (0.8% carbon) when austenite is cooled slowly at approximately 727°C. The name ‘pearlite’ comes from its mother-of-pearl-like appearance under the microscope.

Key characteristics:

- Balanced combination of strength and ductility

- Alternating dark (ferrite) and light (cementite) layers visible under microscope

- Common in medium-carbon steels (0.3–0.6% C)

- Spacing between lamellae determines mechanical properties

- Finer pearlite (faster cooling) = higher strength

5. Bainite

Composition: Ferrite + Fine Carbides

Bainite forms through controlled cooling in the intermediate temperature range of 250°C to 550°C (482°F–1022°F). It has a distinctive feather-like or needle-like microstructure and offers superior strength compared to pearlite while maintaining reasonable toughness.

Key characteristics:

- Stronger than pearlite, tougher than martensite

- Feather-like or needle-like appearance under microscope

- Forms through isothermal transformation or controlled cooling

- Used in controlled-cooling applications and high-strength steels

- Increasingly popular in automotive advanced high-strength steels

6. Martensite

Crystal Structure: Body-Centered Tetragonal (BCT)

Martensite is the hardest microstructure achievable in steel through heat treatment. It forms when austenite is rapidly quenched, preventing carbon atoms from diffusing out of solution. The trapped carbon distorts the crystal lattice from BCC to BCT, creating extreme hardness but also brittleness.

Key characteristics:

- Extremely hard and wear-resistant

- Very brittle without tempering

- Supersaturated solid solution of carbon in iron

- Needle or lath structure visible under microscope

- Forms only through rapid quenching (diffusionless transformation)

- Essential for cutting tools, dies, and wear-resistant applications

7. Retained Austenite

Crystal Structure: Face-Centered Cubic (FCC)

Retained austenite is the portion of austenite that fails to transform during quenching and remains metastable at room temperature. While austenite is normally stable only at high temperatures, certain conditions—particularly high carbon content or specific alloying elements—can stabilize it at room temperature.

Key characteristics:

- Ductile but dimensionally unstable

- Appears as light irregular regions in microscopy

- Common in high-carbon steels (> 0.6% C) and alloy steels

- Can transform to martensite under stress or cold working

- May be beneficial (TRIP steels) or detrimental (dimensional instability)

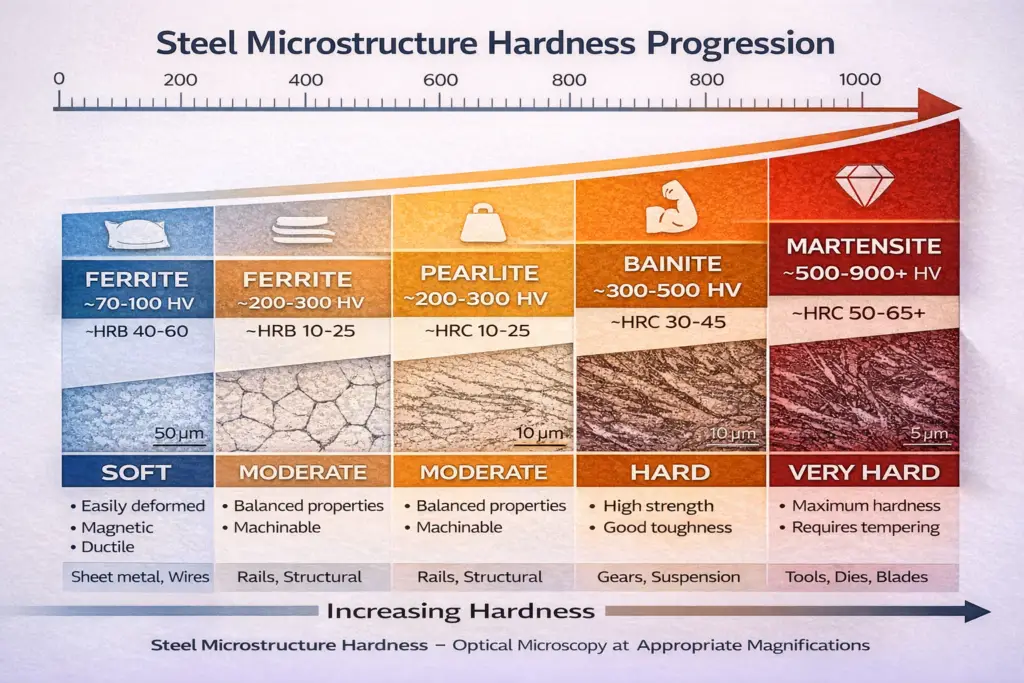

Understanding the Hardness Scale

The hardness progression from softest to hardest follows this sequence:

Ferrite → Pearlite → Bainite → Martensite

Soft → Moderate → Hard → Very Hard

This progression directly correlates with the microstructural arrangement of carbon within the iron matrix. Ferrite’s low carbon content and open BCC structure make it soft and ductile. Pearlite’s lamellar arrangement provides moderate strength. Bainite’s fine carbide dispersion increases strength significantly. Martensite’s supersaturated, distorted lattice creates maximum hardness.

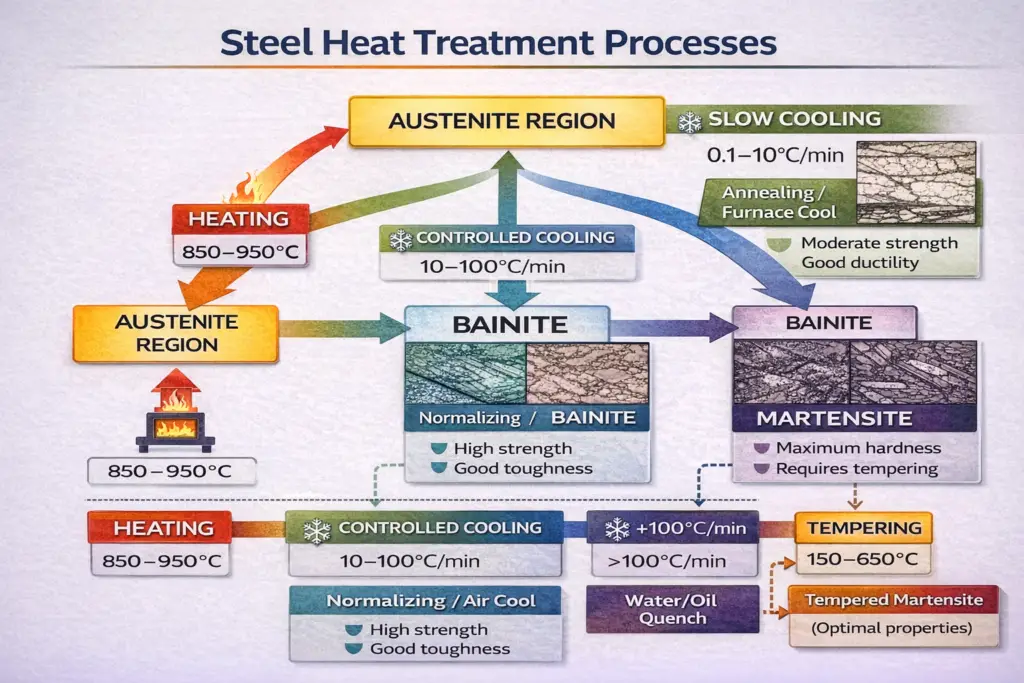

Heat Treatment and Microstructure Formation

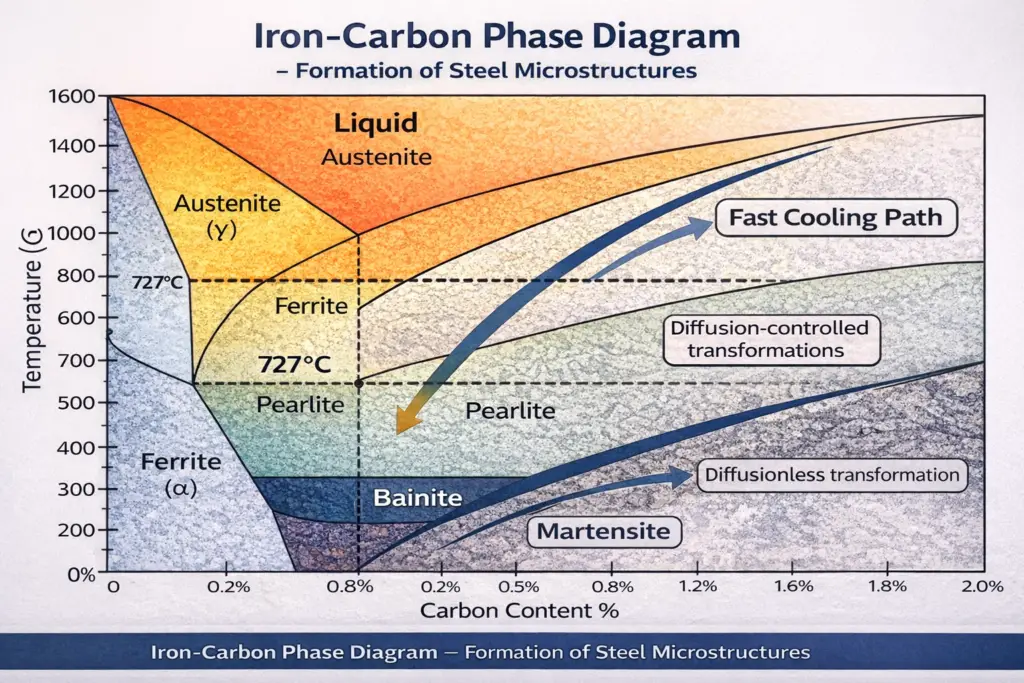

The formation of different microstructure phases is primarily controlled by the cooling rate from the austenite region:

Slow Cooling (Annealing)

Cooling steel slowly from above 727°C allows sufficient time for carbon diffusion. This produces coarse pearlite or a ferrite-pearlite mixture depending on carbon content. The resulting steel is soft, ductile, and easily machinable—ideal for further cold working or as a starting point for subsequent heat treatment.

Controlled Cooling (Normalizing)

Air cooling from the austenite region produces fine pearlite or bainite, depending on the cooling rate and alloy content. This process creates a more uniform microstructure than slow furnace cooling and results in improved strength while maintaining reasonable ductility and toughness.

Rapid Cooling (Quenching)

Rapidly cooling steel by immersion in water, oil, or polymer solutions suppresses diffusion-controlled transformations. Instead, a diffusionless transformation occurs, producing martensite. The quenching medium and part geometry significantly affect the cooling rate and the resulting hardness distribution.

Practical Applications by Microstructure

Different microstructures are selected based on the specific performance requirements of the application:

| Phase | Key Properties | Typical Applications |

| Ferrite | Soft, ductile, magnetic, excellent formability | Sheet metal forming, automotive body panels, wire drawing, structural steel |

| Pearlite | Balanced strength and ductility, moderate hardness | Railroad rails, structural components, medium-carbon steel products, machine parts |

| Bainite | High strength, good toughness, wear resistance | Advanced high-strength steels (AHSS), automotive suspension components, gears, heavy machinery |

| Martensite | Extremely hard, wear-resistant, brittle (requires tempering) | Cutting tools, dies, punches, knife blades, bearing races, wear plates |

Engineering Considerations

Carbon Content Impact

Carbon content is the primary factor determining which microstructures can form and their relative proportions:

- Low carbon (< 0.25% C): Predominantly ferrite, limited hardening potential

- Medium carbon (0.25–0.6% C): Ferrite-pearlite mixtures, good balance of properties

- High carbon (0.6–1.4% C): Pearlite dominant, excellent hardening response

- Very high carbon (> 1.4% C): Hypereutectoid, cementite networks, extreme hardness but brittleness

Tempering After Quenching

Martensite in its as-quenched condition is extremely hard but also dangerously brittle. Tempering—reheating to 150–650°C—is essential for most applications. This process:

- Reduces internal stresses from quenching

- Allows controlled precipitation of fine carbides

- Significantly improves toughness with modest hardness reduction

- Provides property customization through temperature selection

Alloy Element Effects

Alloying elements modify microstructure formation and stability:

- Chromium, molybdenum, vanadium: Form stable carbides, increase hardenability

- Nickel, manganese: Stabilize austenite, improve toughness

- Silicon: Promotes bainite formation, strengthens ferrite

- Boron: Dramatically increases hardenability at very low concentrations

Conclusion

Steel’s remarkable versatility stems from the precise control of its microstructure at the microscopic level. The seven primary phases—Ferrite, Austenite, Cementite, Pearlite, Bainite, Martensite, and Retained Austenite—each contribute unique mechanical properties that can be engineered through careful manipulation of carbon content and heat treatment parameters.

Understanding these microstructure phases is not merely academic—it is the foundation of materials selection and heat treatment specification in modern engineering. Whether designing automotive components that must balance formability with crash performance, selecting tool steels for precision machining operations, or specifying structural members for buildings and bridges, engineers rely on microstructural control to achieve optimal performance.

The bottom line is clear: steel is not ‘just steel.’ It is a carefully engineered material whose performance is determined at the microscopic level. Mastering the relationship between composition, heat treatment, microstructure, and properties is essential for anyone working with this most versatile of engineering materials.

For more technical content on welding, fabrication, and metallurgy, visit weldfabworld.com